Schleiermacher: The Christian Faith, 86-156

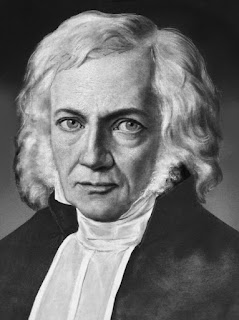

Schleiermacher

will now have a much longer exploration of grace (86-169) as the experience of

vital fellowship that brings moral transformation. The present sense of the Christian

fellowship consists of the need humanity has for redemption. This awareness is

the basis for his concept of Jesus as the Redeemer. Tillich will admit that

much of his discussion of Jesus as the New Being is similar to what

Schleiermacher says here, although he cautions that they are not identical

presentations.[1]

Schleiermacher

begins with Christian consciousness and asks how it posits the redeemer.[2]

He is trying to derive the contents of the Christian faith from the Christian

consciousness. The Lutheran School of Erlangen sought to do something similar.

Such an attempt is an illusion. The event on which Christianity has its basis

is not the regenerated Christian, but the event given to the community in

history. Experience is not the source from which the contents of systematic

theology come. Rather, experience is the medium through which we receive the

contents of the faith.[3]

The theologian needs to hold both the revelatory event in Jesus of Nazareth and

the event nature of the act of faith. Schleiermacher has a loose grip on the

event of the past or the event nature of the present act of faith. In a fine

phrase,[4]

Christ is human nature complete for the first time.[5]

He recaptured the insight of Irenaeus at this point.[6]

His primary interest is in the God-consciousness Jesus possessed. He has

interest in the event of Jesus Christ to this extent. He founded a community

defined by the rule of God among them. Such a community is separate from the

State in that this community has the purpose of deepening the God-consciousness

of each other. Yet, this means he has less interest in the story of Jesus as

related in the Gospels.[7]

Among the challenges in reading Schleiermacher is at this point. The fellowship

of the redeemer must have a historical starting point. Yet, this did not lead

him to the historicity of details in the story of Jesus, the passion or the

resurrection of Jesus. His teaching actually led to the revivalist notion that

found in faith consciousness a guarantee of the historical reality of the biblical

Christ. Thus, one accepts by faith a fundamentalist reading of the Bible. “The

Bible said it; I believe it; that settles it,” I have heard some people say. However,

the thinking of Schleiermacher also led others in another direction in which

the historical contents of the biblical traditions are not important for faith.[8]

He will assume, along with much of the tradition of his time, the unity of the

person and work of Christ.[9]

As

redeemer, Christ (93-99) is the fulfillment of a human nature that already existed

in provisional form in every human being. Our lives are anticipations of the

fulfillment we find in Christ. Christ is the completion of humanity.[10]

He will again affirm that the Redeemer is original in relation to the common

life he founded.[11]

The constant force of his God-consciousness was the true being of God in him.[12]

Thus, our feeling for absolute dependence, our openness to the Infinite, finds

its fullness in Jesus. Here again, we find the strength and weakness of

Schleiermacher. As much as he wants to see Jesus as Redeemer related to the whole

human race, he failed to see that the title “Christ” had this link because of

the cross and resurrection. Paul showed that Jesus became Messiah through his

vicarious suffering for human sins, thereby changing the Jewish hope. He opened

it up with a view to the reconciliation of the Gentile world with Israel and

its God.[13] In

spite of this weakness, we can also express some gratitude that Schleiermacher

offered effective criticism of the notion that the divine and human nature

stand ontologically on the same level. In this theory, the two natures would

have nothing to do with each other apart from their union in the person of the

God-man. Two complete and independently existing essences cannot form a union.[14]

For Schleiermacher, to round out this discussion, the virgin birth is a sign of

a new beginning rather than a condition of that beginning.[15]

The

work of Christ (100-105) consists in his prophetic, priestly, and kingly roles.

He will treat reconciliation and redemption as parallel. Together, they

constitute the work of Christ. The point of reconciliation was to communicate

the God-consciousness of Christ to us. The work of the Redeemer is at the

forefront of the presentation it consists of his taking us up into the dynamic

of his God-consciousness. Reconciliation is simply a special element in the

general work of redemption, namely, the vanishing of the old person and the

sense of guilt that accompanies adoption into living fellowship with Christ.

The reconciling work of Christ confers a sense of the forgiveness of sins. He

breaks with the “magical” satisfaction theory and with the idea of penal

suffering. He is closer to the Pauline idea of an act of reconciliation that

originates in God and through Christ as the world as its target. In historical

theology, this puts him with Abelard and against Anselm. Yet, we must admit

that his presentation carries no reference to the fundamental significance of

the death of Christ that reconciles us to God. However, he does have a place

for the passion of Christ. He understands the suffering of Christ with

reference to the resistance of sin that the work of the Redeemer encounters.

The work of Christ, oriented to the rule of God among us, gave ground to no

opposition, not even to that which resulted in his death. He does, then, link

reconciliation to the obedience of the Son (Romans 5:19). He finds a place in

the form of the faithfulness of Christ to his vocational duty as the Redeemer.

Yet, we will look in vain for anything that corresponds to the statement of

Paul that God reconciles us by the death of the Son (Romans 5:10). He directly

admits that the cross is a secondary element to his notion of the work of

Christ as Redeemer.[16]

He proposes a subjective theory of the atonement. As such, he focused upon the

effects of his death in us. The action of God in the cross is to reconcile us

to God. The death of Christ can truly be for us only within the unity of the

church. We cannot understand atonement without explicit reference to this new

community. Christ suffered the evil of sin for others, facing history of sin in

humanity in order to establish a new community. Atonement is from beginning to

end a description of the human action of Christ, which as such is divine

action. Atonement is the redeeming effect of the entire life of Christ in that

he communicates his unbroken God-relationship to us through the church.

Redemption and reconciliation are identical. Christ dies as a duty of this

calling, as that to which the selfless love with which he pursued his mission

led him. The uniqueness of the cross is that he suffered in especially gripping

fashion. The difficulty of such a

subjective theory is that he will find it difficult to say how the human

situation is different because of the cross.[17]

He concludes this section by saying that the rise of the community is the

result of the perfection and blessedness of the person of Jesus.[18]

The

fellowship of the redeemer (106-112) must express itself in the individual,

which will occur in regeneration (conversion and justification) and

sanctification. He will unite the negative of forgiveness in justification with

the positive side of adoption as a child of God, a notion with which Barth will

agree.[19]

He will also be instrumental in beginning the notion of linking justification

and ethical renewal.[20]

Such a fellowship will lead to a changed life.

Such

a fellowship of the redeemer also leads us into the church (113-163) as mutual

interaction and cooperation. In this section, his dogmatic statements will

relate to the world and to the attributes of God. He will slowly unveil his

basis for a discussion of the Spirit. This discussion occurs through his

valuable insights concerning election and predestination, where God foresees

the faith of individuals. He continues the tradition of discussing individual

appropriation of salvation before he discussed the concept of the church. He

treated the fellowship of individuals with Christ in close relation to

Christology. The doctrine of the church receives treatment only from the angle

of the disposition of the world for redemption.[21]

He also suggests that the fellowship arises out of the innate human inclination

toward fellowship and the related need for sharing. The question is whether

this is enough to justify the presence of the church.[22]

Due to his religious view of the rule of God, linking it to the effects

deriving from Christ as Redeemer, he equated the church with the rule of God

that Christ founded. In light of later theological developments, his position

has obvious weakness in ignoring the apocalyptic nature of the rule of God. Yet,

such an ethical understanding of the concept of the rule of God had the lasting

merit of breaking through the lengthy dominance of a false ecclesiology center

in handling the theme, showing that the rule of God transcends the church. He

showed that the church must relate to the rule of God for its existence.[23]

Among

the most important lasting achievements of Schleiermacher is that he recaptured

a historical reference to human history for the thought election. In this

framework, he related historical calling, or justification, to eternal

election. He therefore transcended the classical form of the doctrine of

predestination in its abstraction and direct relating of election to isolated

individuals. In doing this, he shattered the individualism in the doctrine of

election we may trace back to Augustine and developed in its awful fullness in

Calvin. Instead, he related election as God aiming at the consummation of our

creation and therefore to the totality of the new creation. For reasons unknown

to me, but incredibly suspicious, Barth will not mention that his rejection of

the classical position on election was the same path down which Schleiermacher

walked before him.[24]

He linked the coming of Christ to the new common life of the church that

results from it. Christ and the common life of the church complete human

nature. For him, election and foreordination describes the order in which

redemption finds actualization in each person. For him, the order is the

sequence and relationships of various points in time for incorporation into the

redemptive nexus emanating from Christ. The integration of each person at the

right time into the fellowship of Christ is simply a result of the fact that in

the manifestation the divine work of justifying, its determination is by the

universal world order and is a part of this order. Those not elect at any given

phase of history God simply passed over for this particular point in time but

God has not finally rejected them. Divine providence directs history while he

thus presents the divine election that manifests itself in the justification of

individuals as a process in human history. He will see the incarnation of

Christ as the beginning of the regeneration of the human race. He saw election

as the way to achieve this goal by the divine world government.[25]

Pannenberg will follow Schleiermacher in this view of election and

predestination.

Through

the church, one receives the communication of the Holy Spirit. The leading of

the Spirit is nothing other than the virtue of Christ. Schleiermacher will

stress the common nature of endowment by the Spirit that thus links individual

Christians to the fellowship of the church.[26]

He can emphasize that the unity of the common spirit of the church rests on the

fact that it all comes from the one, namely, from Jesus Christ. Yet, it would

seem that the Spirit is more than simply the common spirit of the church. Thus,

a weakness here is that he does not make the required distinction of the

presence of the divine Spirit from analogous experiences of spirit, such as the

spirit of a nation.[27] At the same time, Schleiermacher is one who,

along with Hegel, presents the idea of the church as a spiritual community.[28]

The

church in its relation to the world has several invariable factors, such as

scripture, ministry, the Lord’s Supper, baptism, the power of the keys, and

prayers. He will say that the divine Word is simply the spirit in all persons.

The ministry of the Word of God is the act of the community and the relation of

the active toward the receptive and the influence of the stronger on the

weaker. The ministry of the Word embraces the whole of Christian life. It only

needs special management for the sake of good order and preservation of the

common consciousness.[29]

I should note that Schleiermacher rightly places his discussion of Scripture

after his discussion of reconciliation. The point here is that our faith in the

reconciliation offered by God in Christ comes prior to our acceptance of the

role of Scripture in the formation of Christian life. Thus, contrary to Barth,

then, consideration of the role of Scripture does not belong in the Prolegomena

of Church Dogmatics. It does not

belong within the doctrine of the church. Rather, scripture remains the primary

witness to the revelation of the reconciling work of God in Christ.[30]

Pannenberg will go with Schleiermacher and turn from Barth at this point. Regarding

Baptism, Barth commends Schleiermacher for being one of the few to see the

problem with infant baptism when he stresses that infant baptism needs its

completion in a personal confession of faith.[31]

Prayer is petition in the name of Jesus. Prayer is the inner link between

wishes oriented to supreme success and the God consciousness. He will

distinguish such prayer from surrender or thanksgiving.[32]

The church in its relation to the world has several mutable elements, such as

the plurality of the churches and the fallibility of the church. He stresses

that the inner unity of the churches consists in taking sides with Jesus and

the life-giving Spirit that thirsts for unity.

[1] Tillich,

Systematic Theology Volume II, 153.

[2]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 280.

[3] Tillich,

Systematic Theology Volume I, 42.

[4]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Vol

2, 41.

[5] Barth,

CD I.2, 134.

[6]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 212.

[7]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 306-310.

[8]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology III,

149.

[9]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, Volume

II, 444.

[10] Barth,

CD I.2, 180.

[11]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 280.

[12]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, Volume

II, 280.

[13]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 315.

[14]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, Volume

II, 385; Jesus-God and Man, 285.

[15] Barth,

CD I.2, 189.

[16]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 408-9.

[17] Robert

W. Jenson, Systematic Theology Volume

I, 186-7.

[18]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 459.

[19]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 212; Barth, IV.1, 594.

[20]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 230-31.

[21]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 24.

[22]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 110.

[23]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 34-35.

[24]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 458-9.

[25]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 450-1, 452.

[26]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology,

Volume III, 3.

[27]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 19, 132.

[28] Peter

Hodgson, Winds of the Spirit, 296.

[29] Barth,

CD, I.2, 62.

[30]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

II, 464.

[31] Barth,

CD IV.4, 188.

[32]

Pannenberg, Systematic Theology Volume

III, 207.

Comments

Post a Comment