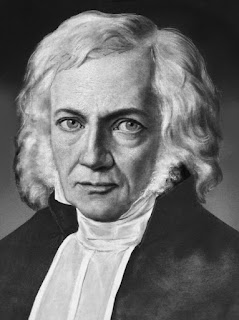

Schleiermacher: The Christian Faith 157-172

The fifth and final discussion of Schleiermacher that focuses on his theology.

The

final two sections of the exposition by Schleiermacher offer to me the

impression that he either lacks interest or is tired. I do not mind. If we look

upon his work to this point, he has made some of the most creative

breakthroughs that continue to inspire theologians today, even if they find

themselves in disagreement. He shifted philosophical theology from it

discussion of natural theology to the philosophy of religion. He also shifted

philosophical theology from the various proofs for the existence of God to a

consideration of philosophical anthropology. The significance of these efforts

is that he has attempted to persuade us that humanity is intrinsically

religious, which means that we depend upon openness to the experience of the

Eternal for authentic living. He tries to show that Christianity is a

particular mode of this experience of the Eternal. Theology has integrity as it

accurately portrays this experience of the Eternal.[1]

He showed the weakness of the two natures theory in Christology, paving the way

for re-thinking that doctrine. He placed the doctrine of election and

predestination in its proper context of the historical working of God in the

church and world. For these reasons, I think we can have some graciousness toward

him if he did not have the interest in paving the way for re-considering

eschatology and the Trinity. He has done enough. We can properly stand upon his

shoulders and learn from him.

The

consummation of the church is in the return of Christ, resurrection, and last

judgment. My impression is that he has little interest in these matters. Schleiermacher

is an example of the opening of modern theology and before the re-discovery of

apocalyptic. He is a worthy example of what it was like before the work on

apocalyptic by Johannes Weiss in the 1890s. He says that we do not need any notion

of the “return of Christ.” Apart from literal exegesis, we have no biblical

warrant for the position that the reunion of believers is conditional on such a

personal return (160). His point is that other biblical statements emphasize

that after death, Christ already unites believers in fellowship with Christ.

Therefore, we have no need of another “return” that unites believers to Christ

in some other way. Nor can he imagine some supposed intermediate state where

Christians await the resurrection of the body, for such a state would consist

in some type of fellowship with Christ. If it were not, it would amount to a

lapse of grace and be an experience of punishment (161). His position has much

to commend it. Exactly what does the return of Christ add to our continuing

fellowship with Christ immediately after death? He also thinks the notion of

the last judgment is primarily to remove from the church the forces that hold

it back from enjoying fellowship with each other and with Christ (162). He

thinks that any notion of blessedness or the vision of God that does not

include communion with others would be insufficient. We are simply too communal

as God made us to not have community to be an important element of our

understanding of the end (163). In an appendix to this section, he thinks that

theology must omit any notion of eternal damnation, for it would create a sense

of emptiness and loss for those who receive the blessing of eternal life. He

has made any discussion of the consummation of human activity focus upon the

individual and the church, separating it from apocalyptic hopes of divine

intervention in natural and world history.

He

is wrestling with the difficult notion of the end of nature and world history,

as we know it. The Newtonian universe he knew has given way to the universe of

Einstein. Neither of them will find the notion of an intervention from God

compatible. The place of apocalyptic in the preaching of Jesus or the early

church was hardly a burning issue for his time. For Schleiermacher,[2] it

will be impossible for the theologian to develop a doctrine of last things, for

our consciousness of God does not include a future that is beyond our ability

to know. His focus on developing a notion of the “consummation of the church”

that arises out of our personal consciousness of God meant anything that he has

to say will be at the periphery of his theology, a fact he readily admits. If

it were important, he says, it would have arisen sooner in his theology. He

accepts that a few statements of Jesus suggest personal survival, and that this

should be enough for us to have the same hope (158). In fact, his concern is

that saying anything about last things and eschatology will take us “away from

the domain of the inner life with which alone we are concerned (159).”

Such

thinking is in sharp contrast to certain strands of theology today. In this Romans commentary, Barth wanted to

recover eschatology for theological thinking. Bultmann will do so as well. The

theologians of hope, Pannenberg and Moltmann, restructured theology so that at

every theme, eschatology must receive serious consideration. The shift is

dramatic. Jürgen Moltmann thinks of theologians who robbed eschatology of its

“directive, uplifting, and critical significance for all the days” that we

spend here, thereby turning eschatology into “a peculiarly barren existence”

that relegated it to “a loosely attached appendix.”[3] He was thinking of Schleiermacher.

Thus, it would seem that much of theology today would disagree with

Schleiermacher that theologians could dismiss the future dimension of Christian

thought quite as easily as he did. In the end (164-169), divine love and divine

wisdom are the goal, as Schleiermacher sees it, of all the works of God,

whether in world, church, or individual. It may well be that we can say little more than

this. It may well be the best hope for humanity and the universe that this

would be true.

Schleiermacher

concludes with a brief discussion of the Trinity (170-172). A popular saying

among ministers and theologians is that as soon as one speaks about the Trinity

or tries to describe or explain it, one enters the realm of heresy.

Schleiermacher is going to say as little as he can. He is tipping his hat to

the tradition, pointing out problems in the classical position, and not

attempting resolution. He has already told us that he cannot complete the

Doctrine of God until the end of his consideration. In a sense, then, even if

brief, his considerations represent his attempt to conclude his theological system.

He has discussed the union of the divine essence with human nature in the

personality of Christ and in the common Spirit of the church. He has pointed us

to the essential elements of the Doctrine of the Trinity. In that sense, the

Trinity is the summit of his reflection on God. Yet, since he begins with the Christian

consciousness, he cannot make the Trinity a constitutive aspect of his

theology. Just as the matter of last things were important to him he would have

brought it up earlier, we might assume the same with the Trinity. If it were

important to him, he would have dealt with it sooner. Clearly, if the Trinity

is to be formative at a deep level in a theological enterprise, then a

theologian accepts the revelatory basis of the teaching. The important point

here is that if one accepts revelation as constitutive for the formation a

theological system, then one can hardly accept the view that one must begin with

Christian consciousness.[4]

Yet, we might pursue a different course as well. We might conclude that we

cannot properly discuss the Trinity until we have discussed Christology, the

relation of Christ and Spirit, and the experience of the Spirit in the community.

Christology is not complete without pneumatology, of course. To take the

approach of Barth and put discussion of the Trinity in the Prolegomena is to

make it seem as if it drops from heaven rather than arises out of an event in

history.[5]

In this sense, then, Schleiermacher may well have a quite legitimate and

reasonable approach to placing discussion of the Trinity at the end of his

considering of The Christian Faith.

He clearly finds it difficult to think of distinctions within the divine

essence. He refers to the divine essence as the Supreme Being. His own insight

of the feeling of absolute dependence creates a problem for formulating the

Trinity. He has said that this feeling connects us with the divine causality of

creation and preservation. We depend upon the prior activity of God for our

existence and the conditions for the fullness of human life. Yet, how would

this feeling relate to the Trinity? Beyond that, other problems confront us in

the formulation of a doctrine of the Trinity. For example, if we are to think

of Father and Son, Son is dependent upon Father. Father begets Son, but Son

does not beget anything. In fact, if the Christian consciousness includes the

divinity of the Son and the divinity of the Spirit, it could lapse into

tri-theism. He thinks that much of the church is secretly on the side of

Origen, who said that the Father is God absolutely, while the Son and Spirit

are divine only by participation in the divine essence. Is Schleiermacher a

modalist?[6]

Such language suggests he might have been. To say the divine essence is present

in Jesus and the Spirit is to suggest this to be the case. The type of

criticism he offers of the classical doctrine of the Trinity trends in the

direction of modalism. He does think the tendency of Trinitarian discussion is

toward showing that the consciousness of Son and Spirit that resides in the

Christian consciousness is not hyperbole.

He does not think we have the terms to adequately deal with this matter.

Equality and subordination, Tri-theism and Unitarianism, seem to keep

presenting themselves. His concern is that many people turn away from such

speculations, but their piety remains faithfully Christian. He thinks the

traditional doctrine needs thorough criticism. Even his positioning of the

doctrine as a harmless appendix (Barth) may help serve the purpose of

re-thinking the Doctrine. Of course, if that happens, the positioning provided

by Schleiermacher is not so harmless. For him, considering the doctrine at the

beginning (Barth) would give the impression that one must accept this teaching

before one can faith in redemption and in the founding of the rule of God

through the divine essence present in Christ and the Spirit. He does not want

to see the shipwreck of individual faith on the difficult shore of the Trinity.

He sees two difficulties. One is the tension between the unity of the divine

essence and its relation to the distinction of the persons. Two is the tension

between the first person as Father and the supposed equality with that which is

terminologically subordinate, Son and Spirit. If one combined the two

difficulties, one might “easily” arrive at a new construction. He suggests

seeking “new solutions.”

Well, he makes it

clear he is willing to go no further. I concur in that I think he has done

enough for the history of theology. He has also hinted at future issues

theology would need to resolve. He has offered his gift. Theologians today

would do well to receive the gift and move forward.

It looks like

Barth took Schleiermacher seriously enough to use him as a foil and do the

opposite.

It looks like

Pannenberg adopted much of the basic insights of Schleiermacher, but updated

them. His theology is so different from that of Schleiermacher because he takes

the event of Jesus Christ seriously. This means he will take revelation as

providing the content of Christian theology rather than the pious consciousness

of the church today. He also takes eschatology and the Trinity and includes

them throughout his theology. Moltmann will do the same. Rahner and Tillich

have some interesting key places where they intersect with Schleiermacher. If

time permits, I would like to see if John Wesley, influenced as he was by the

pietist movement, has some places where he would both push back to

Schleiermacher and would seem to intersect with him.

John Calvin opens

his Institutes of the Christian Religion

with the observation that wisdom in life consists in knowing God and knowing

ourselves. Yet, he finds the knowledge of God and self so closely connected

that he finds it difficult to know which knowledge precedes the other. He

thinks no one can survey oneself without turning thoughts towards God. He

points to the gifts or blessings in life that true knowledge of self will lead

us to consider the source. He points to true knowledge of self as needing to

face the misery and ruin we have made of self and world. This ought to lead us

to aspire to and seek God, the source of wisdom, virtue, and goodness. Calvin

will begin his work in the Institutes

focusing upon the knowledge of God we have in revelation. However, I wonder if we do not see in Schleiermacher what happens

when we begin with knowledge of self, which he finds so intertwined with God

that we cannot know one without the other. As Calvin puts it, our being subsists

in God. As Schleiermacher might put it, our finitude will find fulfillment and

meaning in the Infinite. The fragment that is our life will need to find its

place in the picture God is painting. The little storyline of our lives will

need to find its place in the larger story God is telling. He hopes that such a

procedure will help the secular person reconsider the role God and the

religious community might play in their lives.

Yes, I think this is a worthy objective.

George, it is fascinating to me, and speaks to the enduring greatness of Schleiermacher, that he becomes as influential (in an indirect way) for the doctrines that he neglects as he does for the doctrines he celebrates. This realization is maybe the highlight of your reflections on Schleiermacher and really does illustrate his importance. where would we be if he had not dismissed eschatology and the Trinity (or at least relegated them to a diminutive status). I do not mean that insincerely. It speaks to his greatness, insofar as even the voids he leaves, become influential. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comments. I do hope that when you can make some time you will read his Speeches. It gives anyone interested a good way to experience his approach to secularity. His The Christian Faith requires much more pondering and plodding through. In any case, after reading him this time, I wondered if his approach to eschatology might not be right. After all, Barth went from Romans, where it looked like eschatology would be central, to CD, where he seems to replace eschatology with Christology. He also famously turned away from Pannenberg and Moltmann because of it. As important as the Trinity is to me, could it be that its placement in the prolegomena is a bit much? In any case, yes, his historical significance is set. Today, although some of his solutions to theological issues continue to have their influence, his significance is more in approach than in content.

ReplyDelete